|

|

Anna Hyatt Huntington, Meet New York City

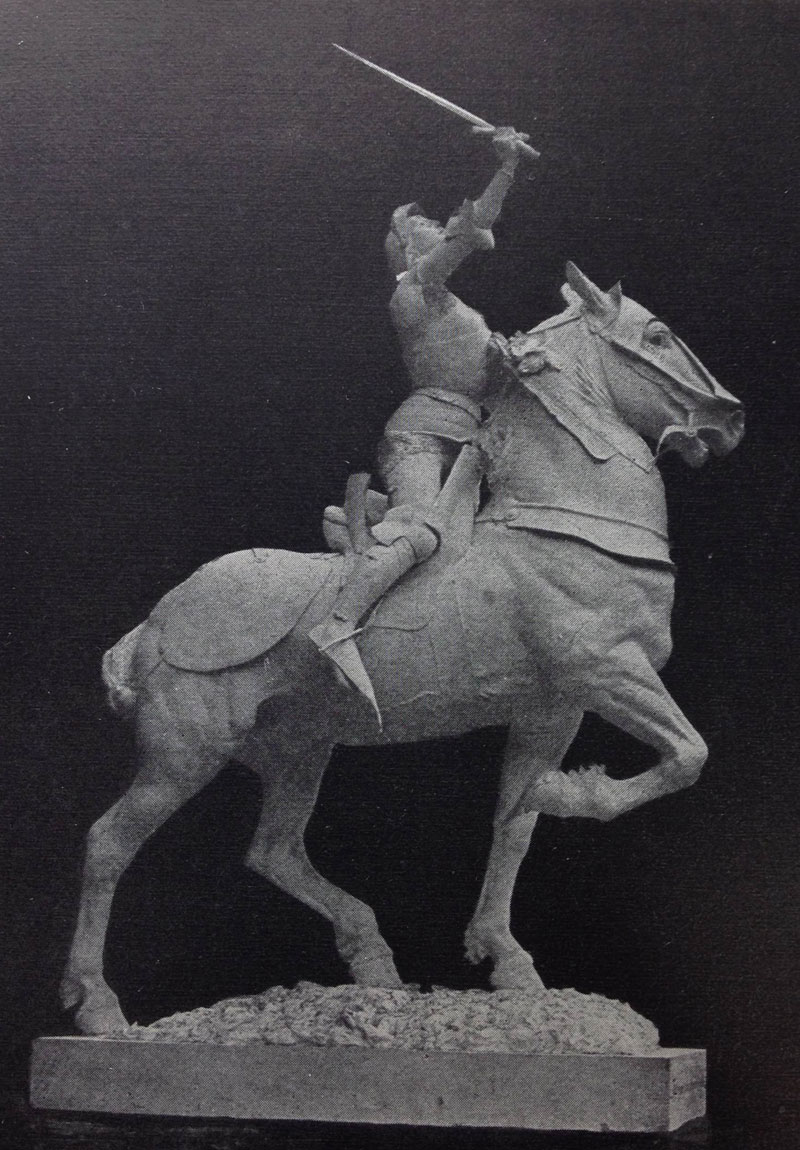

By Anne Higonnet, Ann Whitney Olin Professor, Department of Art History, Barnard College and Columbia University New York City met Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973) when she arrived in 1902 with three systems that could support her unlikely aspiration to public sculpture. Only in New York could she have found such a thriving market for small sculpture, such a network of ambitious arts institutions, and so many unconventionally professional women, all in the same place. By brilliantly combining the city’s opportunities, she achieved one pioneering success after another between 1903 and 1936. Those achievements left their mark on the city, forgotten but waiting to be rediscovered. A Market for Small SculptureBy starting small when she arrived in New York City, the almost unknown and vulnerable artist named Anna Vaughn Hyatt was unlikely to offend anyone.1 Fresh from the Boston area, where she had sold small animal sculptures through the fine metalwork firm Shreve, Crump & Low, she was primed to appreciate the similar, but much more extensive, chances to make and sell statuettes in New York. Several skilled foundries had flourished in the New York area since the 1850s. They cast, stocked, and sold enough editions of high quality statuettes to make a private sculpture market possible. In addition, the city’s cultural institutions sponsored the creation of many medals or commemorative plaques, each of which required a sculptor, and which were distributed in multiples. Anna Hyatt Huntington worked with several foundries over the course of her New York career, including Roman Bronze Works, the Kunst Foundry, and Gargani & Sons, but during her crucial early years in the city she dealt primarily with Gorham & Company, located at Fifth Avenue and 47th Street, whose foundry was in Providence, Rhode Island. Gorham stocked her work and promoted it through catalogues and exhibitions. The company included many of her statuettes in their group exhibitions, and gave her a solo presentation in 1914. She received royalties, which varied according to the piece and its price.2 At sale prices ranging from about $25 to $335,3 statuettes enabled a single woman to earn her living without being forced to confront gender barriers. Sales of forty- to fifty-inch pieces were rare, but these commanded $1,500. Some of her small animal sculptures sold hundreds of copies, notably Yawning Tiger. Others were adapted into saleable functional objects, like bookends and letter-openers. Gorham editions of her early works were still selling in 1936, though some had been discontinued.4 By 1912, Anna was reported to earn more than $50,000 a year, placing her among the highest paid professional women in the United States. She later said the amount had been exaggerated. However inaccurate, the report vividly conveys her reputation for financial independence. Anna Hyatt Huntington introduced her work into public institutions with the proverbial “thin end of the wedge.” The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences commissioned a group of animals for its paleontological department by the end of 1902.5 The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired Two Horses, Winter, (aka Winter Noon) in 1906. The prestige of this acquisition was in inverse proportion to the 7 1/4 inch high size of the sculpture. Daniel Chester French, the visionary sculpture curator of the Metropolitan, advocated the collection of work by living artists, a policy financially feasible because of the statuette market. The Metropolitan acquired two more of her works by 1912, both of which measured less than foot high. Cultural InstitutionsThe Metropolitan Museum of Art was only one among many New York City institutions determined to make their home the undisputed cultural capital of the United States. When Anna Hyatt Huntington began her New York career, some institutions, such as the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (now the Brooklyn Museum), the National Academy of Design, the New-York Historical Society, New York University, and Columbia University were established, while others were recent, like the New York Zoological Park (now the Bronx Zoo) and the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. All of them contributed to New York City’s bid for national and even international stature.6 Museums, monument committees, academies, societies, ribbons, medals, prizes, commissions, galas, and pageants abounded in New York City, organized by citizens with similar civic aspirations. In their rush to reach lofty goals, they were willing to take some risks. Anna Hyatt Huntington was one of them. Year by year, she accumulated official honors, notably a bronze medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, a silver medal at the 1915 Pacific American Exposition in San Francisco, the Rosette of Public Instruction from the French Government in 1915, the Rodin Gold Medal in Philadelphia in 1917, two Saltus sculpture prizes in 1920 and 1922, and was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1922. Each award made her a more acceptable choice for the next. HeroineParis remained the power center of the art world. Anna Hyatt Huntington knew that to attract New York’s full attention she needed to be recognized by the Paris Salon. Feeling confident that she had acquired a distinctively American style, she pushed herself to the next level by going to France for long stays between 1906 and 1910. There, she seemed to be still working on more animal subjects. Then came a surprise. Anna Hyatt Huntington told stories about her long search for the perfect horse. Candidates were rejected because they were too small or too delicate. Finally the artist found one massive enough. Her stories hinted at a dramatic increase in the scope of her ambitions. They also deflected attention away from what was truly radical about her next project. The monumental sculpted horse she exhibited at the 1910 Paris Salon was indeed astonishingly large. It proved, however, to be only an accessory to its rider, Joan of Arc. Clad in armor from head to toe, she rose from her steed to raise a weapon toward heaven. Of course, the figure’s evident martial valor was veiled by the theme of a pure girl who obeyed religious voices to save her nation, and died a martyr’s death at the stake. Anna Hyatt Huntington had challenged the Parisian art establishment with her version of a sacred French subject. Despite the Salon jury’s doubts about whether she could have executed the life-size sculpture all by herself, they awarded her an honorable mention. Had she chosen the much less institutionalized, avant-garde alternative to Salon art, she could not have returned to New York with as persuasive a qualification for public art. A subject like Joan of Arc was perfectly suited to the idealizing and patriotic classicism of Beaux-Arts New York. At the 1910 Salon, J. Sanford Saltus saw Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Joan of Arc. An executive of Tiffany & Company, the New York luxury jewelry and design firm then at the height of its artistic reputation, he knew the esthetic of the statuette. His thoughts, like Anna Anna Hyatt Huntington’s, had turned to public art. In 1913 the committee staged an exhibition about Joan, packed with hundreds of past and present images, including Anna’s 1910 sculpture, probably in the form of a photograph. The committee then chose Anna to create a larger-than-life bronze Joan of Arc. It wasinaugurated at a mass public ceremony at Riverside Drive and 93rd Street in 1915. Everyone from the committee’s official historian to the most casual critics said that the historical accuracy of Joan’s armor was essential to the sculpture’s significance, and that the accuracy was the responsibility of Bashford Dean, the socially prominent scholar, collector, and founder of the Metropolitan’s Arms & Armor department. In fact, this was barely true.7 Correspondence in the archives of the Arms & Armor department at the museum show that it was committee members, not Anna Hyatt Huntington, who sought out Dean’s advice, and Dean hardly paid any recorded attention to her project, delegating research to an assistant. Most decisively, comparison between newly re-discovered photographs of the 1910 Joan of Arc and the1915 version demonstrate that the armor was already almost entirely designed by 1910.8 The true change between the 1910 sculpture and the 1915 monument was the composition of Joan’s body. In the first, Paris version, the body was flexed at its joints. The New York figure reaches straight upward out of her stirrups, aligned with her horse’s forward motion. Anna Hyatt Huntington had reasons to collude in the disclaimers of her authorship. They camouflaged her audacity, and made it more palatable for her to leverage the Riverside Drive Joan of Arc’s public fame. It was the first public monument in New York City by a woman. It was also, after many female allegories and muses, the city’s first monument to honor a real woman. GoddessAnimal sculpture had provided the pretext to dare an equestrian statue, the supreme genre of sculpture since ancient Rome. It must also have inspired Anna Hyatt Huntington’s early 1920s choice, among all divinities, to create two versions of Diana. Artemis, renamed Diana by the Romans, was the goddess of wild animals and of the hunt, as well as an archetype of female autonomy. The subject of Joan of Archad challenged Anna to find a new and personal way to express a holy French theme that had become popular and patriotic only in the previous century. More dauntingly, Diana was the subject of revered, canonical sculptures dating back to archaic Greece, among them, close by in New York City, an already-iconic version by the great Beaux-Arts sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. In response to the long history of Dianas, Anna’s most successful, 1922 Diana of the Chase was an ascending swirl of graceful energy. Her Diana aimed a bow at the sky. Caught just after the instant of the shot, her head is still turned in the direction of her target, one arm still retracted and fingers folded from the string’s pull. Casts of the 1922 Diana became defining symbols of the institutions that displayed them, including the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, Cambridge; the Huntington Art Gallery, Pasadena; Syracuse University, New York; the National Academy of Design, and New-York Historical Society, whose copy has recently been beautifully restored. In most cases these casts of the Diana were originally installed outdoors, amplifying their public impact. Reduced versions were also produced, such as a 1932 mixed-metal version designed in 1926. From 1925 to 1928 an anonymous miniature version of the Diana even ornamented the hood of a car named the Diana Moon.9 Career WomenEvery aspect of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s New York career—professional, critical, and emotional—was sustained by exceptional women. She collaborated with Abastenia St. Leger Eberle on a sculpture that they displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and which won her first public notice for large-scale work. For years she shared an apartment with another sculptor and close friend, Brenda Putnam. She participated in two all-women’s art exhibitions in the 1910s, one of which was documented by the pioneering photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. Her portrait was painted in oil by Marion Boyd Allen in 1915. While she received many positive reviews from men, she received as many from women. Without reservation or qualification, female critics dared to pronounce that Anna Hyatt Huntington’s work was great. In 1921, for example, Corinne Updegraff Wells singled her out from a group of New York women artists who “besides the exquisite objects of art one naturally associates with feminine genius” were doing “herculean monuments and gigantic figures,” and pronounced her “a sculptor of the first rank.”10 Anna Hyatt Huntington attributed the origins of her artistic inspiration to her two grandmothers as well as to her mother, Audella Beebe Hyatt. Anna began sculpting to emulate her sister, Harriet Randolph Hyatt; Harriet made a lovely marble portrait bust of Anna at the age of 16, now in the collection of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York. Anna’s mother came to New York for months at a time to manage Anna's and Brenda Putnam's apartment.11 From Anna’s adolescence until her mother’s death in 1932, they exchanged letters regularly, sometimes more than once a week. Anna cherished these letters and preserved them in her archives. Gifted with so much support, as well as the will and wit to act on all her opportunities, not to mention her remarkable strength and height, Anna deliberately crafted a remarkable artistic persona. Whenever she posed during her early career, she grasped a sculptor’s tool in her hand and stood near a work in progress so that its idea would seem to emanate from her. For a photograph signed by “Misses Selby N.Y.”, taken in about 1910, she holds an implement, while a sculpted horse in soft focus seems to crown her. In a film about the technique of stone carving made for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1930, she subordinated her physical self to her task, head tightly wrapped, body smocked, wielding a tool continually, precisely, as she finishes the head of a life-size jaguar. When she made a sculpture of her own hand, cast in 1935, it also held a tool, on which she signed her initials: “A.H.H.”. The portraits she staged of herself projected creative power. MarriageIn 1923, Anna Vaughn Hyatt became Anna Hyatt Huntington. Her marriage to Archer Milton Huntington was the most important personal decision of her life. Anna and Archer stayed a very happy couple for his remaining thirty-two years. Marriage also had a deep impact on Anna’s profession. Her union with Archer brought Anna’s early career to its culmination. He was an institutional network unto himself, the founder and funder of over a dozen cultural institutions. In New York alone, he was behind the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Numismatic Society, and his favorite brainchild, the Hispanic Society of America. Archer’s wealth allowed Anna to have many of her best early works cast or carved on large scales, and donate them to museums. Her 1915 Joan of Arc, for example, was re-cast by Gorham in 1926 for $5,800 and given to the San Francisco Legion of Honor Museum, where it still stands.12 Her two big jaguars, Jaguar and Reaching Jaguar, which she created at the Bronx Zoo between 1902 and 1906, were cast life-size in bronze in 1926, and given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They were also carved life-size in stone and presented to the Bronx Zoo. Life-size bronze casts of her 1922 Diana of the Chase were donated to the National Academy of Design, the New-York Historical Society, Syracuse University, as well as other museums in the United States and abroad. BeastsAnna Hyatt Huntington had launched her career by specializing in animal subjects. She was nominally trained by George Grey Barnard, Hermon Atkins MacNeil, and Gutzon Borglum, all of whom included animals in their repertoires. More substantively, she learned about animal anatomy and movement at the zoo with her father. Animal sculpture was considered a minor genre, and therefore relatively unthreatening. The genre’s reputation gave many critics license to praise her lavishly because the praise seemed already qualified. For example, in 1929 Parnassus Magazine pronounced, “Anna Hyatt Huntington displays some of her living animals which are only surpassed by the great Hellenistic masters of animal life.” Throughout her career, Anna Hyatt Huntington announced a natural affinity for animals. Casual snapshot photographs pictured her feeding buffalo at the zoo, riding horses, walking dogs, or herding cows. She said she empathized with the spirit and personalities of animals. Somehow, though, the animals she chose to sculpt during the earlier years of her New York career belonged to the wilder, fiercer fringes of nature. Among all the monkeys she could have chosen for her early large monkey plaque, she picked the most surly and muscular. At the Bronx Zoo, she was attracted to deadly, stalking carnivores: jaguars, tigers, and lions In these earliest animal pieces, energy is expressed in tensile, sinuous, straining, resistant forms. Jaguars and monkeys reach aggressively, a tiger’s yawn stretches its limbs and torso into a single taut line, butting goat heads collide upward, fighting bulls lock horns against the ground. No matter how natural Anna Hyatt Huntington claimed her relationship to animals was, it is one thing to love animals, and quite another to make art about animals. The style of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s animal work remained consistent until the early 1920s. During her work on her husband’s Hispanic Society courtyard, between 1923 and 1927, she incorporated animals into eight small, decorative plaques, and created ample, calm guardian groups for the magnificent piazza ensemble. Between 1934 and 1936, in preparation for a major retrospective exhibition that traveled across the country from 1936 to 1939, she added lyrical birds and playful animals to her repertoire, notably a new monkey series. The forms of these sculptures were more detailed, and their compositions more expectable. She also began to experiment with aluminum. Aluminum was light and therefore made her traveling exhibition easier to manage. Aluminum’s bright silvery esthetic must also have appealed to her personally, because when she cast sculptures of her hand, her husband Archer’s, and her father-in-law Collis P. Huntington’s in 1935, she chose aluminum rather than the more traditional bronze Continuing her experiments with new media, she later cast a 1934–1936 sculpture of two gamboling greyhounds in a latex-ceramic compound. Architectural SculptureUntil now, the least well-known phase of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s career has been the years she dedicated to the Hispanic Society of America’s courtyard. New research shows that as soon as she and Archer Milton Huntington met in 1921, they began to dream of a sculpture program for the enclosure, a huge empty space splendidly bounded by Beaux-Arts buildings at Broadway and 155th Street. Indeed, it might even be said that their courtship was expressed in terms of sculpture, waxing and waning according to the magnitude of the projects they were discussing.13 By 1922, Anna had made a second Joan of Arc for the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, also in upper Manhattan, in a delicate, linear, medieval style very different from her earlier work. Immediately after her marriage in 1923, she began to work in earnest on the Hispanic Society project. She incorporated medieval and courtly themes dear to her new husband, who in addition to his philanthropy was an eminent scholar of Spanish literature and translator of the great medieval epic, El Cid. At first Anna worked in the style of the 1922 Saint John the Divine Joan of Arc, adapted to the small scale of decorative plaques. These works, love-offerings to Archer, have recently been located and identified in the collection of the Hispanic Society of America. For the majestic equestrian monument at the heart of the courtyard program, however, a larger-than-life El Cid, whose base was inscribed with lines from Archer’s El Cid translation, Anna returned to the heroic figurative style of her earlier Joan of Arcs. She flanked El Cid with four life-size male figures. The modeling of El Cid was finished in 1925, and parts of the program continued to be cast and installed into the early 1930s. The whole courtyard installation is one of the most imposing, and least known, in New York City. Ironically, it was completed just in time for 155th Street to begin to seem far north and isolated from the rest of Manhattan. In 1927, Anna Hyatt Huntington was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Illness disrupted her life and sent her away from New York City in search of milder weather. For years she could not work as she had before, although sculpture continued to be cast. In some fundamental way, the New York era of her career began to wind down. When her traveling exhibition started its tour in 1936, her early New York was over. A great sculpture patronage career awaited her elsewhere, which is another story. A Century LaterGoddess, Heroine, Beast anticipates the 2015 centennial of the installation of Joan of Arc on Riverside Drive. It was an historic moment for Anna Hyatt Huntington, and for New York. One hundred years later, the city can take pride in a long tradition of unlikely artists, who, over and over, have renewed New York’s culture. Footnotes1 To avoid confusion, this essay refers to its subject as Anna Hyatt Huntington, in deference to her choice to change her name both personally and professionally in 1923. Until 1923, however, she was known as Anna Vaughn Hyatt, and signed her work Anna Vaughn Hyatt. Back2 Letter negotiating prices and royalties from William Drake, Gorham & Co. Bronze Division, to Anna Hyatt Huntington, Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries (SUL herafter) July 13, 1933. Back3 This range of Hyatt’s1920 prices was listed with the suggestion they be increased. Letter from William Drake at Gorham & Co. to Anna Hyatt Huntington, October 30, 1936. SUL. Back4 Letter from Anna Hyatt Huntington to her mother Audella Beebe Hyatt, April 1925. Hispanic Society of America archive. Letter from Gorham & Co. to Anna Hyatt Huntington, July 9, 1925. Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Syracuse University. Letter from William Drake at Gorham & Co. to Anna Hyatt Huntington, October 30, 1936. SUL. Back5 Anon. “Society Girl, Who Has Won Fame as a Sculptor, Here to Execute a Commission for Brooklyn Institute.” Brooklyn New York Daily Eagle, Jan. 4. 1903, p. 2. Back6 Her own father, Alpheus Hyatt, had been among a generation of men, albeit in the Boston area, who professionalized amateur avocations by developing institutions. A student of Louis Agassiz, Alpheus Hyatt taught paleontology and zoology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1870-88) and at Boston University (1877-1902), was custodian and later curator of the Boston Society of Natural History, and helped found the Woods Hole Center for Marine Biology. 7 At the time it was not known that Dean’s ideas about early 15th century armor, of which almost none survives, was based as much on his fantasies as on authentic evidence. Back8 “JEANNE D'ARC BY ANNA VAUGHN HYATT.: First Life-Size Equestrian ...” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); May 7, 1911, pg. SM3. This research was carried out by Morgan Albahary, Caitlin Beach, and Sonia Coman. Moreover, Anna Hyatt Huntington had several armor models to work with in France, especially the immensely popular 1837 Jeanne d’Arc sculpture by the princess Marie d’Orléans and the more recent, also very popular, 1896 book frontispiece Jeanne d’Arc illustration by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel. 9 Letter from Anna Hyatt Huntington to her mother Audella Beebe Hyatt, July 28, 1924. The Hispanic Society of America archives. 10 Corinne Updegraff Wells, “Personality Flashlights,” The New York Sun, December 29, 1921, p. 12. Back11 Letter from Brenda Putnam Nov. 12 1932, addressed to “A.H.H.” Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Syracuse University, Box 51. Back12 Letters from Gorham & Co. to Anna Hyatt Huntington, July 9, 1925, and July 12, 1926. SUL. Back13 Letters between Anna Vaughn Hyatt and Archer Milton Huntington, Sept. 11, Sept. 24, Nov. 3, Nov. 10 1921, Dec. 15, 1922, Box 35, SUL. Back

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Yawning Tiger, 1902-06; cast 1919–21. Bronze; 8 3/8 x 28 1/3 x 7 3/4 in. | 21.27 x 71.76 x 19.69 cm. Collection Syracuse University Art Galleries, gift of Linda Witherill (1993.039). Image courtesy Syracuse University Art Galleries. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Two Horses, Winter, (aka Winter Noon), c. 1903; cast before 1906. Bronze; TK in. | TK cm. Photo Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, J0034862. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Goats Fighting, 1905; cast before 1912. Bronze; 10 1/4 x 14 5/16 x 7 1/2 in. | 26 x 36.4 x 19.1 cm. Collection the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.51). Photo copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Tigers Watching, c. 1906. Bronze; 7 1/4 x 13 x 6 3/4 in. | 18.4 x 33 x 17.1 cm. Collection the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1906 (06.303). Photo copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Joan of Arc, 1910. Reproduced in American Numismatic Society, Joan of Arc Exhibition Catalogue (New York: Wynkoop. Hallenbeck, and Company, 1913). ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Joan of Arc, 1915. John V. Van Pelt, Architect. Bronze and Mohegan granite; 20 ft. 4 in. x 6 ft. 1 in. x 12 ft. 3 in. (6 m. 19.8 cm x 1 m 85.4 cm x 3m. 73.4 cm). Riverside Park at 93rd Street. Collection of the City of New York; gift of the Joan of arc Statue Committee. Photo by the Media Center for Art History, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery. ×

Joan of Arc unveiled at Riverside Drive and 93rd Street, New York, December 15. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-DIG-ggbain-20588]. ×

Augustus Saint-Gudens (1848-1907). Diana, 1893–94; this cast, 1894 or after. Bronze; 28 1/4 x 16 1/4 x 14 in. | 71.8 x 41.3 x 35.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art,New York,NY U.S.A., gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1985 (1985.353). Photo copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Diana of the Chase, 1922; cast between 1923 and 1939. Bronze and marble; 99 x 33 x 29 1/2 | 251.5 x 83.8 x 74.9 cm. The New York Historical Society, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Archer B. Huntington (1939.252). Photo courtesy The New-York Historical Society. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Diana, 1932. Aluminum, gold plate and silver plate. 32 1/2 x 9 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. | 82.5 x 2.1 x 21.6 cm. Collection Syracuse University Art Galleries, gift of the Estate of Anna Hyatt Huntington (0019.043). ×

Marion Boyd Allen. Portrait of Anna Vaughn Hyatt, 1915. Oil on canvas; 65 x 40 in. | 165.1 x 101.6 cm. Collection Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, Lynchburg, VA. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington’s Mrs Aalpheus Hyatt, aka The Artist’s Mother [Audella Beebe Hyatt], 1910. Photograph by Peter A. Juley & Son. Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, J0034923. ×

Portrait of Anna Hyatt Huntington by The Misses Selby Studio, c. 1910. Courtesy Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Hand of Anna Hyatt Huntington, cast 1935. Aluminum; 12 7/8 x 4 9/16 x 2 1/2 in. | 32.7 x 11.6 x 6.4 cm. Collection The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY (D1013). Photo by Mark Ostrander, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery. ×

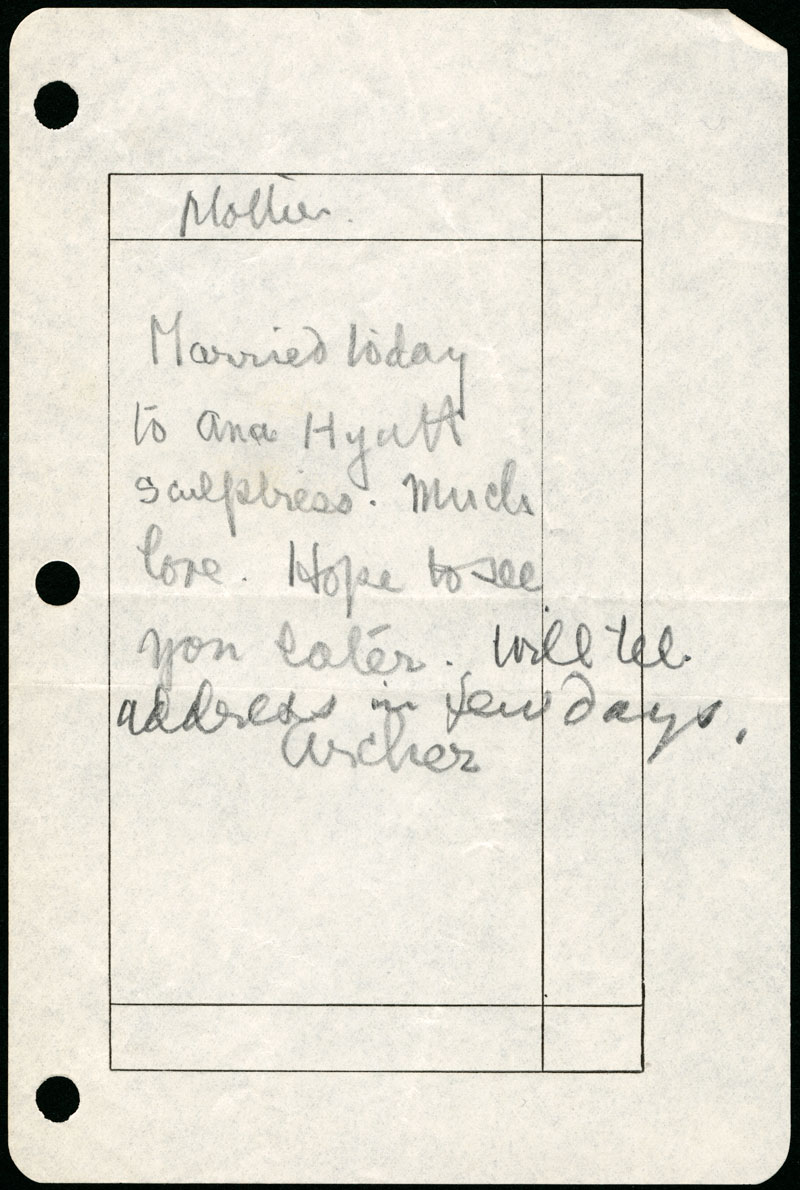

Telegram text from Archer M. Huntington to his mother, Arabella Huntington, 1923: “Mother, Married today to Ana Hyatt sculptress. Much love. Hope to see you later. Will tel. address in few days. Archer.” Courtesy Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Monkey Group, 1902-06. Bronze; 40 1/8 x 22 3/16 x 10 5/8 in. | 102.4 x 56.4 x 27 cm. Collection The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY (D980). Photo by Mark Ostrander, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery. ×Anna Hyatt Huntington. Animal Flagpole Plaques, 1928-29. Designed for the Hispanic Society of America. Bronze; each approx. 4 3/16 x 8 5 1/16 in. | 13.2 x 21.1 cm. Collections the Hispanic Society of America. Photo by Mark Ostrander, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery.

Head of a Bear

Head of a Bull

Head of a Camel

Head of a Donkey

Head of a Goat

Head of a Jaguar

Head of a Llama

Head of a Wild Boar ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Greyhounds Playing, 1936. Latex-ceramic compound; 18 1/2 x 21 x 10 in. | 47 x 53.3 x 25.4 cm.] Collections the Hispanic Society of America (LD78). Photo by Mark Ostrander, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. Joan of Arc, 1922. Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York City. Photo by Gerald Sampson, courtesy The Wallach Art Gallery. ×

Anna Hyatt Huntington. El Cid, 1929. Bronze; 12 2/3 ft. | 5.07 m. Audubon Terrace, The Hispanic Society of America. Photo by the Media Center for Art History, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University. × |