|

|

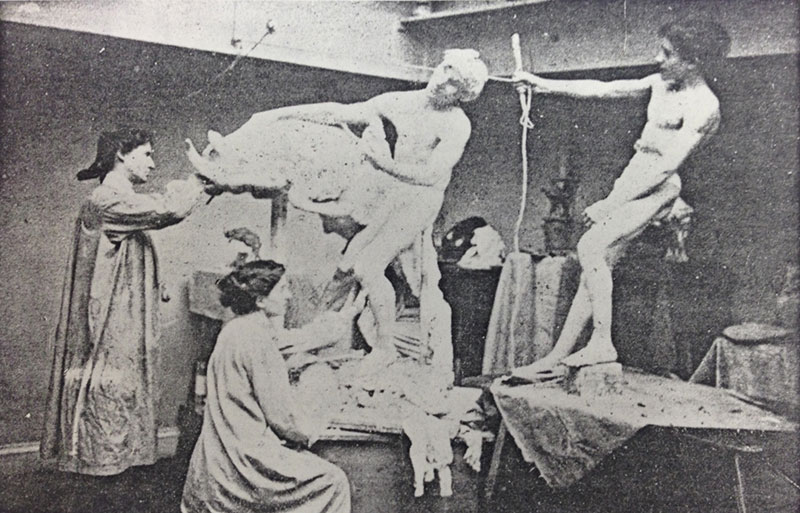

Female Sociability and Solidarity: The Circle of Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington, 1903-1936By Sonia Coman Always a magnetic personality, Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington attracted around her a circle of artistic and cultural colleagues. Many of her collaborators and friends were exceptional women who shared her challenges and opportunities. Her relationships with these women, always significant, whether brief or spanning many years, included creative collaborations with fellow woman sculptors, group exhibitions of women’s art, some of which were organized by national clubs and associations of women artists, and friendships with socially powerful women, with whom she was involved through social events and art patronage. Women critics chose to write about Hyatt Huntington and her work. Women painters, sculptors, and photographers created portraits of the artist. Hyatt Huntington selected and emulated female models, from contemporary actresses like Maude Adams to women sculptors of the recent past like Marie d’Orléans, to older historical or mythological figures such as Joan of Arc and Diana. These wide-ranging connections wove a network of female sociability and solidarity that affirmed the creative power and professionalism of women artists. Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington’s mother, Audella Beebe Hyatt, was a practicing artist who specialized in landscape watercolors and who illustrated the books of her husband and Anna’s father, the paleontologist Alpheus Hyatt.1 The artist’s parents inspired her to pursue an artistic career, nurtured a dedication to naturalism, and encouraged her passion for animals. Anna could particularly identify with her mother’s commitment to a career as a woman artist. Providing illustrative plates for her husbands’ scientific books, the artist’s mother set an example of professional collaboration within the family. Anna’s first artistic partnership occurred in her teens, when she was still dedicated to the study of music. Her sister Harriet asked Anna to help her complete a sculpture of a boy with a dog. Harriet worked on the human figure and Anna on the animal.2 Exhibited and purchased, the sculpture was a success.3 In that same year, Harriet carved a portrait bust of her sister in marble.4 This sculptural portrait reflects the personal bond between the two sisters and calls to mind the “power of sisterhood” exemplified by Berthe Morisot and her sister Edma, who affirmed their artistic ambitions by working side by side, using each other as models, and exhibiting and selling their works together.5 Harriet’s portrait of her sister also attests to an early awareness of their talents and a precocious ambition to record their professional paths and personal connection.Hyatt Huntington (then using the name Anna Vaughn Hyatt) undertook another artistic partnership with Abastenia St. Leger Eberle. Their collaboration debuted in 1904 with the public display of their first jointly created sculptural piece, Men and Bull, at the St. Louis World Exposition, for which both artists were awarded a bronze medal.6 They decided to continue their collaboration and exhibited a new co-authored piece, Boy and Goat Playing, at the Spring Exhibition of the Society of American Artists in 1905.7 Men and Bull and Boy and Goat Playing share the theme of interaction and play, calling attention to the collaborative aspect of their making. According to Bertha Smith, the project surprised its audience because the sculptors declared their intention to create a joint authorial entity through several collaborative projects.8A photograph shows the two women working side by side in the same studio. Hyatt Huntington is working on the animal, Eberle is working on the human figure. From this photograph we know that the model for the figure of the boy was, in fact, a woman. This situation bespeaks the centuries-old tension between the proper modesty of women and their professional ambitions in the fine arts. In a now classic essay, Linda Nochlin argued that women artists were not given equal chances to achieve the same level of excellence as their male colleagues because they did not have access to the same art education.9A major component of this training was the study of the male nude, long denied to women. The “Ladies Life” class, offered in 1868 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, allowed women to draw the (female) nude model for the first time in the United States; from 1877, male models were studied as well.10 Whether or not this long-fought battle was even considered in the studio of Hyatt and Eberle in the 1900s, the two artists decided to emphasize the feminine collaboration that was at the core of their project by choosing a woman as a model for the sculptural piece. The photograph, however, directs our gaze to the props specific to the profession: sculpting tools, lighting devices, and drapery. The studio therefore complicates the associations of an all-female environment with domesticity, because the furnishings highlight the function of the studio as a working space. Hyatt Huntington’s and Eberle’s early pieces met with public success. Bertha Smith, a prolific journalist who privileged topics related to professionally successful women, wrote admiringly about their sculptures. She attributed the accomplishment to personal and professional traits which the two artists had in common. Among other similarities, both abandoned music for sculpture as a medium; in sculpture, both preferred simplifying forms in order to fuel their expressive potential.11 As Smith noted, their collaboration in sculpture marked a moment when both were negotiating and defining their approach to the medium and their engagement with the material presence of the work of art.12 By 1910, the two women advanced their careers separately, although they would continue to share exhibition venues. Eberle’s later work was received as an expression of the “American rhythm” of everyday life and as a commentary on the socio-political issues of the time.13 Hyatt Huntington expressed her engagement with national identity differently, by implicitly contrasting her identity with dominant French artistic institutions and themes. In 1910, she gained recognition as a young American sculptor at the Paris Salon. In 1915, prior to the formal entry of the United States into World War I as an associated power to the Allies14, Hyatt Huntington’s Joan of Arc monument was unveiled in New York City in the presence of Jean Jusserand, the ambassador of France, who delivered an address. Despite their differences, however, both Hyatt Huntington’s and Eberle’s work was bound up with difficult aspects of feminine identity. Eberle “appealed to the public’s fears and anxieties” by displaying her controversial White Slave sculpture at the 1913 Armory Show.15 White Slave represents a young woman (in the nude) abducted by a menacing (clothed) man. Hyatt’s Joan of Arc statues represented her French heroine in full armor. Hyatt Huntington’s was the first monument of a female historical figure by a woman artist in New York City. Bertha Smith was not the only woman author, critic, and activist who chose to write about Hyatt Huntington’s art and career. It is not coincidental that numerous articles about Hyatt Huntington’s distinctions and participation in exhibitions of women’s art clubs and associations were signed by women. Corinne Updegraff Wells, who declared Hyatt Huntington “a sculptor of the first rank,”16 was a regular contributor to women’s magazines and a successful businesswoman who ran her own advertising agency.17 Through writers like Wells, Hyatt Huntington and her work were brought to the attention of women in other professional fields. They contributed to a public acceptance and celebration of art, and particularly sculpture, as a domain in which women and men could be equally successful. Critical response to Hyatt Huntington’s work included at least one woman photographer and one woman editor. Photographs of Hyatt Huntington’s work by the pioneering photojournalist Frances Benjamin Johnston documented the sculptor’s work in its context and particularly in public display venues. A photograph by Johnston of Hyatt Huntington’s “Girl and Urn” sculpture shows the piece framed by columns, next to another figural sculpture, among the profuse plants of the Touchstone gardens, on the occasion of the May 1919 Touchstone sculpture exhibition. Johnston’s photographs called attention to the resonance of Hyatt Huntington’s work with their surroundings, and to their lyrical quality, an aspect of her sculpture also emphasized by critics Jean Royère and Emile Schaub-Koch in their 1930s writings about Hyatt Huntington.18 The “Girl and Urn” piece shows the figure touching the side of the base on which the sculpture stands. This explicit reference to the raw material of her medium displays the self-awareness of the artist. This aspect is present in her animal sculptures, too, where the figure of the animal is often a foil to an amorphous mass of marble.19 The Touchstone magazine that featured Johnston’s image was established and published by Mary Fanton Roberts, a journalist and art critic who also founded the Decorative Arts magazine and acted as editor of The Craftsman magazine.20 Hyatt Huntington shared studios with women sculptors. Although not collaborating on co-authored pieces, she worked side by side with artists who shared her passion and ambition. When she moved to New York, Hyatt Huntington met Harriet Frismuth, another sculptor who specialized in small bronzes, at the Art Students League, where they decided to share a studio.21 They exhibited together several times, including in women’s art exhibitions. Hyatt Huntington and Frismuth, as well as Eberle, were selected to exhibit small sculptures in the “Woman’s Room” – a large gallery filled with paintings and sculptures of artists deemed representative of women’s art – at the World’s Fair of 1916, next to paintings by Mary Cassatt.22 In her article about this section of the Exposition, Annie Nathan Meyer, a promoter of higher education for women and the sister of the activist Maude Nathan, explained the significance of the “Woman’s Room”: unlike previous editions, the 1916 World’s Fair did not have a “Woman’s Building” to segregate women artists, but included hundreds of women artists among male artists in various galleries curated according to criteria other than gender.23 The role of the “Woman’s Room” was, then, to single out art that featured both professional excellence and feminine creativity. Hyatt Huntington’s selected pieces asserted an art-making process that was inseparable from her experience of sharing both the working space and the venue of public display and recognition with other women artists. Solidarity and emulation were components of success. Hyatt Huntington also shared an apartment and a studio at 49 West 12th Street with her friend the sculptor Brenda Putnam.24 Katharine Ward Lane (later Katharine Ward Weems), who was a student of Putnam’s at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, recalled one afternoon when Hyatt Huntington came over to tell her about her new shared studio and to talk about sculpture.25 In 1923, Anna Vaughn Hyatt and Archer Milton Huntington were married in that studio; Putnam was one of the very few who attended the ceremony.26 Anna’s marriage to Archer did not affect her relationship with the two women artists. Over the years, she had shown a mix of friendship, maternal protection, and professional encouragement toward Putnam and Lane. In a simplified scheme, Putnam was her equal – they were the same age, were roommates for many years, and appreciated each other’s work -, while Lane was her pupil – she was much younger and had much to learn from Hyatt Huntington. However, the artist thought of both as her protégées. She untiringly encouraged and supported them, scolded them at times, and visited their homes and their studios frequently. They are repeatedly mentioned in Hyatt Huntington’s letters to her mother. From these letters we know that Hyatt Huntington was happy for Lane when she received an Honorable Mention at the Paris Salon of 1928, like Hyatt did eighteen years before.27 Two years after Hyatt Huntington became the first woman sculptor to be elected a full member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1932, she nominated Lane for membership and suggested that Malvina Hoffman, a younger and successful woman sculptor, be nominated, too, thus initiating a lineage of women sculptors within the Academy.28 To her mother, Hyatt Huntington expressed her worries when Putnam was mourning her late mother and Lane was undergoing a crisis in her self-confidence as an artist: “[they] seem (…) so introspective that nothing is spontaneous, (…) but maybe [it’s] a phase only.”29 Hyatt encouraged her friends to be true to themselves and to assert their creativity in order to overcome personal and professional problems. One of Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington’s favorite images of herself was a still photograph from Sculpture in Stone. Premiered on 18 February 1930, Sculpture in Stone is the third film in a series produced by the University Film Foundation for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Staging a confrontation between artist and animal, the film vividly illustrates how Hyatt Huntington wanted to be perceived: at work in her studio, with a sculptor’s tool in her hand, face to face with her life-size jaguar. The theatricality of the film was not lost on contemporary viewers; the press emphasized its dramatic qualities.30 The medium of film underscores the effect of naturalism that the artist strove for in her three-dimensional work. Hyatt Huntington was interested in rendering movement: in her animal sculptures, jaguars stretch, bulls fight, and hounds jump. By removing extraneous information, the film channels the viewer’s attention to the psychic connection between the image of the artist at work and the representation of the jaguar in action. In conjunction with Sculpture in Stone, the series produced From Clay to Bronze, which features Katharine Ward Lane. In these films, the two women cast bronze and carve marble: actions typically associated with male prowess. Articles about the films reminded readers of the entrenched notion of sculpture as a male-dominated activity,31 emphasizing that Sculpture in Stone and From Clay to Bronze present women as exemplars of the profession. No self-portraits of Hyatt Huntington are known, unless we consider her sculpture of her own hand as one,32 but – or because - she was depicted by fellow artists, especially women, in sculpture, painting, photography, and film. As a model, Hyatt Huntington collaborated with artists to convey an image of herself that embraced both her femininity and her identity as an artist. A paradigmatic image for this fusion of femininity and professionalism is her photographic portrait produced by the studio of Misses Selby in New York around 1920. A positive review of Lily Selby’s studio, written only a few years after Selby’s arrival in New York from London, describes the “impression” of entering “the home of an artist” when visiting her photographic studio,33 evoking Hyatt Huntington’s own combination of home and studio. Selby and Hyatt Huntington championed the idea that a woman could confidently combine art practice and domesticity in their self-presentation. In the portrait, with a sculpting tool in her hand, Hyatt Huntington’s figure is aligned with that of her sculpture of a horse in the background. Part of a centuries-old tradition of portraits of artists at work, in the studio, surrounded by their art, with a tool indicative of their medium, this image is similar to other portraits of American women sculptors of the time. One example is a photograph of Brenda Putnam that shows her holding a sculptor’s tool next to her bust portrait of a child – the genre that Hyatt Huntington most admired in Putnam’s work34. What sets apart these images of Hyatt Huntington, Putnam, and other women sculptors of their generation is the assertive embrace of a strong, but elegant femininity that is not at odds with, but integral to their identity as professional and successful artists. Marion Boyd Allen, a resident of Boston and student of the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, painted a portrait of Hyatt Huntington in 1915. She is shown working on the clay model for her equestrian Joan of Arc which was to be installed as a public monument in Riverside Park in New York City the following year. Her profile seems to be completed by the visible half of a lion’s face modeled in relief and hung on the wall behind her in her Annisquam summer studio.35 Referring to the “strong and muscular,” but “lean and elegant” body of the artist, the historian Laura Prieto noted that “Hyatt [Huntington] is graceful and feminine, but not on display” in Allen’s portrait.36 This powerful image of Hyatt Huntington, like Selby’s photographic portrait, exhibits the fusion between the artist’s commitment to relentless hard work and her lifelong dedication to observing, sculpting, and caring for animals. Allen’s portrait also exemplifies Hyatt Huntington’s self-identification with the figure of Joan of Arc – a project she pursued in various guises throughout her long career. Hyatt Huntington began her long association with Joan of Arc in 1909-1910, when she modeled her first equestrian Joan for the Paris Salon; her commitment to the Joan theme continued for decades. She commissioned small-scale bronze casts of her 1915 Joan design for various occasions, most often in the context of social and cultural patronage. In February 1917, she impersonated Joan of Arc at the “Fête des fous,” a medieval-themed pageant organized by the Architectural League of New York. Hyatt Huntington’s appearance represented the “thrill of the evening:”37 lights lowered and Hyatt Huntington, clad in full armor and riding a white horse, entered the room. According to an article about the pageant, “a big American flag was unfurled at the back of the French heroine and saint [Hyatt Huntington] and as the lights were turned up the notes of the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ were sounded and the entire audience, standing, sang the national anthem.”38 She was wearing a steel helmet and a “floating drapery” patterned with the French fleur de lis.39 A significant moment of that pageant was the staging of a tableau centered on Hyatt Huntington/ Joan of Arc.40 Among those present at the pageant were affluent members of New York society, such as, for example, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, a patron of the arts and an accomplished sculptor herself.41 Whitney was one of several attendees who had a box for the pageant42 – an equivalent of a loge at the opera. Hyatt Huntington’s arrival was announced by two heralds wearing coordinated costumes, impersonated by Maud Kahn and Malvina Hoffman,43 the sculptor whom Hyatt Huntington recommended for nomination to the Academy of Arts and Letters. Although not yet extremely wealthy, she was already a pivotal member of a highly influential and highly educated community that accepted and celebrated women who were both artists and patrons. Her theatrical performance of Joan at the pageant embodied the connection between her sculptural work and her social activity. In embracing performance as a mode of self-expression, Hyatt Huntington emulated popular actresses of her time and particularly Maude Adams, who starred in a memorable performance of Joan of Arc in 1909 at Harvard. Adams performed the lead role of Friedrich Schiller’s Die Jungfrau von Orleans in English translation on the Harvard Stadium, for the benefit of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, then recently founded and called the Germanic Museum, with a cast and crew that numbered more than a thousand persons.44 Hyatt Huntington had a personal connection to Harvard. Her father, the zoologist Alpheus Hyatt, graduated from the university in 1862. She might not have seen the performance, but, given her familial ties to the university and her close relationship with her mother who lived in Massachusetts, she must have at least been aware of the show and of its advertisements. A poster shows Maude Adams as a fully armored Joan of Arc on horseback. This representation of the actress as Joan might have inspired Hyatt Huntington’s appearance at the 1917 pageant: both rode a white horse and donned a blue drapery with the fleur de lis pattern. Also displayed as a poster for the event was Alphonse Mucha’s painting Maude Adams as Joan of Arc, which, unlike the other poster, does not depict the heroine in armor or on horseback, but in a flowing medieval dress surrounded by vegetation. At Adams’ request, Mucha’s painting was later displayed in the lobby of the Empire Theater in New York City, where the actress performed regularly.45 Adams’ identification with Mucha’s image suggests that the actress, like Hyatt Huntington, embraced this role as an alter-ego. However, the images of Joan that Hyatt Huntington and Adams seem to have preferred are strikingly different: if the sculptor’s Joan is in full armor, on horseback, and ready for battle, impersonating her fighting spirit, the actress’ and Mucha’s Joan is clad in graceful drapery and framed by a profusion of flowers, expressing the virginal and mystical nature of the heroine. Hyatt Huntington’s appropriation of the Joan of Arc persona took both public and family forms. Her impersonation of the French heroine took place in the midst of New York high society; the unveiling of her public monument in 1915 was attended by the ambassador of France and by powerful American women such as Mina Miller Edison, the wife of Thomas Edison and a member and once national chaplain of the Daughters of the American Revolution association.46 In the early stages of the Riverside monument project, however, it was the private world of the artist’s family that witnessed and influenced the shaping of the artist’s conception of Joan. Following the traditional practice of first modeling the figure in the nude and subsequently adding the costume, Hyatt Huntington made an intermediate version of her equestrian Joan, between the armored 1910 and 1915 versions, in which the figure of the heroine is nude. Hyatt Huntington’s niece, the daughter of her sister Harriet, posed on a barrel in her aunt’s studio for this representation of Joan47 that was not to be publicly displayed, but which was critical for the execution of the 1915 armored version. For the artist, the “core” of Joan was the woman underneath the armor and specifically, the youthful body of her niece, who, as a relative, stood for the artist’s own identification with Joan. The medieval French heroine was extremely popular in early 20th century America, where it became a favorite subject in the arts, in popular culture, and in the diplomatic relations between the United States and France. Joan of Arc was adopted as a symbol by women activists and suffragettes. It is no coincidence that the New York Times page that featured the unveiling of Hyatt’s monument in 1915 published photographs of the event next to an image of three hundred delegates of the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage, some of whom were riding horses, on their way to the White House, to propose a suffrage amendment to the Constitution.48 The connection between the suffragettes and the popular appropriation of Joan of Arc dates back to the 19th century. The suffragist and abolitionist Sarah Moore Grimké translated Alphonse de Lamartine’s biography of the maid of Orléans in 1867 and chose to illustrate it with an image of a sculpture of Joan by the French princess and sculptor Marie d’Orléans (1813-1839).49 Grimké was a model for the suffragists who rode to the White House in 1915 and Marie d’Orléans may well have been an inspiration for Hyatt Huntington. Not only had the Orléans princess created a Joan of Arc statue in 1837, but afterwards, the sculpture had become tremendously popular through its reproduction in prints, advertisements, textiles, commercial labels, and especially in reduced statuettes.50 Long after the princess had died, moreover, portraits of her continued to identify her with her Joan of Arc, and many of those portraits were also mass-reproduced. Ary Scheffer’s portrait of the princess, painted two years before her premature death at the age of 26, already shows her with a professional tool in hand, seated near her sculpture, of which only a fragment is visible. The simple and elegant dress, the tool, and the nearby sculpture are elements that Huntington later used for her own self-presentation in Allen’s painting, Selby’s photograph, and the still from the Sculpture in Stone film. Hyatt Huntington’s embrace of the Joan of Arc theme took a new form in the early 1920s when she turned to the subject of the goddess Diana. The Joan and the Diana themes are interconnected because both reflect the artist’s love of animals, represent a strong female role model, and evoke, in the artist’s creative process, the inspiration she drew from the world of performance, theater, and cinema. Just as Hyatt Huntington’s Joan rode a horse, so her Diana was rendered with a hound at her feet. In a curious connection between her Joan and hounds, Hyatt Huntington donated a small bronze cast of her 1915 Joan as a trophy for the annual dog competition of the Scottish Deerhound Club of America.51 Huntington cherished images that showed her in the company of animals, particularly, in later life, photographs of her feeding and walking her deerhounds. And just as Hyatt Huntington had found inspiration for her Joan in the work of the actress Maude Adams, so the artist may have modeled at least one of her Dianas on the film actress Bette Davis. In the 1980s, the elderly actress declared she was 18 when she posed for a woman sculptor for a fountain piece called Spring; soon after, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts announced having discovered that statue: not Spring, but a Young Diana of either 1923-24 or 1926 by Hyatt Huntington.52 The artist connected the Joan and the Diana figures and fashioned them as her alter-egos. The artist grounded their conception, presentation, and reproduction in her affirmation of feminine creative power. This creative power depended on her familial and social circles. In her circles, femininity was compatible with the exceptional intellectual and physical prowess required by professional sculpture. The sociability among the women in Hyatt Huntington’s circle led to their solidarity, which became a driving force in their professional success. Footnotes1 Entry on “Huntington, Anna Vaughn Hyatt” in Dictionary of Women Artists, Delia Gaze, ed., vol. 1 (Taylor & Francis, 1997). Also, “Women Artists from the Cape Ann Museum Collection: A Survey Exhibition,” October 24, 2009 – January 31, 2010, gallery guide, accessed December 30, 2013. http://huntingtonbotanical.org/Rose/Subrosa/42/annahyatt.htm Back2 Bea Whyld, “Anna Hyatt Huntington and the Huntington Great Danes” in Subrosa, no. 42, 2005, Huntington Botanical, accessed December 8, 203. http://huntingtonbotanical.org/Rose/Subrosa/42/annahyatt.htm Back4 Robin Salmon, Sculpture of Brookgreen Gardens (Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 114. The bust was donated by a son of the artist to Brookgreen Gardens. Back5 Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot’s Images of Women (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 7-8; 18. Back6 Bertha H. Smith, “Two Women Who Collaborate in Sculpture” in The Craftsman, vol. VIII, no. 5, August 1905, 623. Also, “A Sculptress who has Caught the American Rhythm” in Current Opinion, vol. LV, no. 2, August 1913, 124. Back9 Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Woman Artists?” (1971) in Women, art and power: and other essays (New York: Harper & Row, c1988), 147-158. 10 Christine Havice, “In a Class by Herself: 19th Century Images of the Woman Artist as Student” in Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 2, no. 1, 1981, 38. Back13 “A Sculptress who has Caught the American Rhythm,” 124. Back14 The French Republic, the British Empire, and the Russian Empire formed the Triple Entente or the Allies. Back15 Susan Casteras, “Abastenia St. Leger Eberle’s ‘White Slave’” in Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 7, no. 1, 1986, 32. Back16 Corinne Updegraff Wells, “Personality Flashlights,” The New York Sun, December 29, 1921, 12. Back17 Chairman’s note/ masthead, The Rotarian, vol. LVII (57), no. 2, 1940, 5. Back18 Jean Royère, Le Musicisme Sculptural: Madame Archer Milton Huntington (Paris: A. Messein, 1934); Emile Schaub-Koch, Madame Anna Hyatt Huntington et la statuaire moderne (New York, 1936). Back19 For more information on Huntington’s animal sculpture, see http://annahyatthuntington.weebly.com/anna-hyatt-huntington-and-her-big-cats.html Back20 “Mary Fanton Roberts Papers, 1880-1956,”Archives of American Art, accessed December 8, 2013. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/mary-fanton-roberts-papers-8457 Back21 Josephine Withers, Women Artists in Washington Collections (The Gallery, 1979), 53. Back22 Annie Nathan Meyer, “’The Woman’s Room’ at the World Fair” in The International Studio, vol. LIX (59), August 1916, 29. Back24 Katharine Lane Weems, Odds Were Against Me (Vantage Press, 1985), 35. Back25 Weems, 35. Katharine Lane Weems dedicated her memoir to Charles Grafly, Brenda Putnam, and Anna Hyatt Huntington. Back26 “A. M. Huntington and Anna Hyatt Wed at Studio” in New York Tribune, March 11, 1923. Back27 Letter of Anna Hyatt Huntington to Audella Beebe Hyatt, undated, presumably July 1928. The Hispanic Society of America archives. Back28 Letter of R. Sanda to Mrs. William Vanamee, September 17, 1934. Archives of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Back29 Letter of Anna Hyatt Huntington to Audella Beebe Hyatt, November 1928. The Hispanic Society of America archives. Back30 A. J. Philpott, "Two Motion Pictures Show Processes of Sculpture" in Boston Globe, 15 February 1930. Back32 For more information on Huntington’s casts of her sculpted hand, see http://annahyatthuntington.weebly.com/tools-for-understanding-anna-hyatt-huntingtons-hands.html. Back33 Alfred Bishop Hitchins, “The Misses Selby: Some Account of Their Work and Methods” in Wilson’s Photographic Magazine, vol. 50, 1913, 414. Back34 Letter of Anna Hyatt Huntington to Audella Beebe Hyatt July 6 [possibly 1929]. The Hispanic Society of America archives. Back35 “Portrait of Anna Vaughn Hyatt,” The Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, accessed December 8, 2013. http://maier.randolphcollege.edu/Obj519?sid=15&x=1433. The portrait is now in the collections of the Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, where Anna Vaughn Hyatt was a visiting artist in 1922, before her marriage. Back36 Laura R. Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Harvard University Press, 2001), 153. Back37 “Architects Stage Mediaeval Masque” in New York Times, February 27, 1917. Back40 “Architects Stage Mediaeval Masque.” Back41 Ibid. Among the monuments designed by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney is the Victory Arch in Madison Square, New York City. Back42 “The Fête of the Architectural League was a Brilliant Medieval Pageant.” Back43 “The Fête of the Architectural League was a Brilliant Medieval Pageant” in Vogue, April 15, 1917. Back44 “Maude Adams to Rehearse Next Week for Harvard Stadium Presentation” in New York Times, May 5, 1909. Back45 “Maude Adams (1872–1953) as Joan of Arc, 1909,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed December 8, 2013. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/20.33 Back46 “The Equestrian Statue of Joan of Arc Designed by Miss Anna V. Hyatt and Erected on Riverside Drive” in New York Times, December 12, 1915. “Mina Miller Edison,” National Park Service, accessed December 8, 2013. http://www.nps.gov/edis/historyculture/mina-miller-edison.htm . Back47 Beatrice Gilman Proske, “The Monument: Joan of Arc by Anna Hyatt Huntington” in Joan of Arc: A Keepsake Commemorating the Restoration and Rededication of the Joan of Arc Monument, Riverside Drive and Ninety-Third Street, October 30, 1987, 7. Also, “Joan of Arc Memorial,” Riverside Park, City of New York Parks & Recreation, accessed December 8, 2013. http://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/riversidepark/monuments/819 . Back48 “The Equestrian Statue of Joan of Arc Designed by Miss Anna V. Hyatt and Erected on Riverside Drive.” Back49 Dominique Goy-Blanquet, ed., Joan of Arc, a Saint for All Reasons: Studies in Myth and Politics (Ashgate, 2003), 131. Back50 “Looking at Lunchtime: Joan of Arc bronze [acquired by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute]” in Bennington Banner, December 5, 2008. Back51 Correspondence between C. Nelson Weese, the Secretary of the Scottish Deerhound Club of America and Mahonri S. Young, Acting Director of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, September 1951 – January 1952. Archives of the Museum of Art of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. Back52 “Bette Davis Eyes?” in New York Times, Late Edition, June 17, 1982. The connection between Bette Davis and Hyatt Huntington’s Diana sculptures remains to be investigated. Back

Harriet Hyatt, Anna Vaughn Hyatt, c. 1895, marble. Collection of Brookgreen Gardens. (1990.002). Image courtesy of the Brookgreen Gardens. ×

"Miss Hyatt and Miss Eberle at Work in Their Studio,” photograph, The Craftsman, vol. VIII, no. 5, August 1905, p. 629. ×

Frances Benjamin Johnston, “Girl and Urn” by Anna Vaughn Hyatt, photograph, The Touchstone, July 1, 1919, p. 289.] ×

Still photo from 1930 film, Sculpture in Stone, produced by the University Film Foundation for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Photo courtesy of Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. ×

Portrait of Anna Hyatt Huntington by The Misses Selby Studio, c. 1910. Courtesy Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. ×

Peter A. Juley & Son, Brenda Putnam, American sculptor, 1890-1975, photograph. Archives of American Art. ×

Marion Boyd Allen. Portrait of Anna Vaughn Huyatt, 1915. Oil on canvas; 65 x 40 in. | 165.1 x 101.6 cm. Collection Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, Lynchburg, VA. ×

“The Romance of the Sculptress and the Multi-Millionaire”, press clipping. Courtesy Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. ×

“Harvard University, the Stadium, Tuesday night, June 22d, under the auspices of the German Department of the University, Charles Froham presents: Maude Adams in Joan of Arc.” Cincanniti; New York: Strobridge Litho. Co., 1909. Electronic reproduction. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard College Library Digital Imaging Group, 2011. Copy digitized: Houghton Library: TS 239.290.11. ×

Alphonse Mucha, Maude Adams (1872–1953) as Joan of Arc, 1909, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 20.33. ×

Plaster model of Joan of Arc in the nude (anatomical model), photographed by the studio of C. Ording in 1931 in New York City. Negative model no. 4467. Archives of The Hispanic Society of America. Courtesy The Hispanic Society of America. ×

Ary Scheffer, Portrait of Marie d’Orléans, 1856, oil on canvas. Collections du Musée Condé, Chantilly. PE 799. ×

Photograph of Anna Hyatt Huntington with her hounds. Courtesy Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. × |