|

Imagine, 1985

|

The Outdoor Museum: A Short History of the NYC Parks Monuments and StatuaryBy Jonathan Kuhn, NYC Parks Director of Art & Antiquities The first commemorative sculpture placed in a New York City park no longer survives. It was an equestrian portrait of King George that stood in Bowling Green (the city's oldest park), where it became a convenient target of Colonial revolutionaries. On July 9, 1776, incited by the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in New York at City Hall Park, a mob ventured south on Broadway, and proceeded to topple this bronze symbol of tyranny. While New York's public monuments may have suffered since then from weathering, vandals and pigeons, this was the last known instance of the destruction of a public monument based on its content. Eighty years later, on July 4, 1856, thousands gathered in Union Square to witness the dedication of the George Washington equestrian statue by Henry Kirke Brown, now the oldest extant sculpture in a public municipal park in New York. The following day The New York Herald Tribune commented: “It is we hope the commencement of the good work of beautifying our great metropolis, the people of which are fond of art and willing to encourage it.” The sculpture had been sponsored by citizen contributions, not tax dollars, and it was the beginning of a vast civic outdoor museum that would reflect the shifting interests and artistic styles of the ensuing decades. No other sculptures were placed in the city's parks until the following year, when the State chartered the Board of Commissioners of Central Park in 1857. Charged with oversight for building this massive new park, as well as management of existing parks and plazas in Manhattan, the Board soon found itself beset with requests to erect statuary in the nascent parks system, but without a formal process of review. The Board of Commissioners established a committee for Statuary, Fountains and Architectural Structures, charged with the mission of ensuring that such features "harmonize with the landscape" and guided by the principle that "the park throughout is a single work of art." Proposed sculptures were reviewed on a case by case basis, with a limited number approved in the 1860s--notably Emma Stebbins' Angel of the Waters at the Bethesda Fountain and John Quincy Adams Ward's Shakespeare. Further downtown, a massive monument to Major General William Jenkins Worth was erected in a small plaza at the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue, and marks this distinguished military leader's grave. At Union Square, Washington was joined in 1870 by Henry Kirke Brown's companion statue of Abraham Lincoln. All of these artworks (other than the Angel of the Waters sculpture) adhered to a funding model of private commissions. With the creation of the Parks Department in 1870, greater attention was given to the principles and procedures for the acceptance of sculptures. A directive in Central Park specified that portrait and commemorative sculptures be placed only along the Mall or near park entrances, and "sculptured works of art of dramatic or poetic interest" were to be placed in a manner that they did "not interfere with the views of the Park." Confronting pressure to erect monuments without provision for adequate historical perspective, park officials decreed that "no statue commemorative of any person shall be accepted until after a period of five years from the death of such person." This dictate has in large part been adhered to since then, with the notable exceptions of inventor Samuel Morse (in 1871) and James Stranahan (the "father of Brooklyn Parks") whose sculpture was unveiled in 1896 at the northern entrance of Prospect Park. One non-human subject, Balto the sled dog, also violated this dictate in 1925, and was said to be "unmoved" by his sculpture's unveiling. To assist it in the review of artistic merit and design, the Parks Department relied in this era on the advice of experts from the newly formed National Academy of Design, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Upon the consolidation of Greater New York in 1898, the new charter gave the Art Commission (today the Public Design Commission) legal authority over the review and acceptance of monuments and works of art on municipal property. Though certain statuary and monuments in the city's parks have a decorative, allegorical or purely aesthetic function, the collection is predominantly commemorative in nature. Nearly a third of the monuments collection are war memorials, from modest plaques to the massive Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Brooklyn. J. Q. A. Ward's Seventh Regiment Memorial (1869-1974), consisting of a solitary soldier, became the prototype for numerous Civil War monuments in the town squares of America. Later Alfred G. Newman's The Hiker, an iconic Spanish-American War figure dedicated in Staten Island's Tompkinsville Park in 1916, would inspire more than 20 copies across the United States. In the category of portraiture, Randolph Rogers' seated effigy of William Seward at Madison Square Park's southeast corner, dating to 1876, was the first monument in the parks that depicted a New Yorker. More often than not commemorative portrait sculptures in our parks were of persons of international significance and impact, such as the author William Shakespeare, composer Giuseppe Verdi, or independence leaders Simon Bolivar, Benito Juarez and Mahatma Gandhi. Many have represented cultural icons of immigrant groups whose nationalities have gained a significant foothold in the life of New York City, from Scottish authors Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott to Juan Pablo Duarte, the father of the Dominican Republic. Regardless of era or intent, many of the best of artists of their time have been enlisted to realize these monumental sculptures. A new American sculptural idiom of studied naturalism flowered under such 19th-century sculptors represented in the collection by J. Q. A. Ward (Indian Hunter, Roscoe Conkling, Henry Ward Beecher etc.) Daniel Chester French (Marquis de Lafayette in Prospect Park), Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Admiral Farragut and General William Tecumseh Sherman) and Frederick MacMonnies (Nathan Hale, General Slocum, etc). Leading 20th-century artists are well represented too, including Anna Hyatt Huntington (Joan of Arc, Jose Marti), Paul Manship (the Osborn Gates, Alfred E. Smith Memorial Flagstaff, Rainey Gates), Louise Nevelson (Night Presence IV), Raphael Ferrer (Puerto Rican Sun), George Segal (Gay Liberation), and Robert Graham (Duke Ellington)). Venerable artists such as Elizabeth Catlett (Invisible Man: A Memorial to Ralph Ellison), as well as mid-career practitioners Eric Fischl (Soul in Flight: The Arthur Ashe Memorial), Mac Adams (The New York Korean War Memorial/Universal Soldier) and Allison Saar (Swing Low: The Harriet Tubman Memorial) have given a contemporary sensibility to this commemorative tradition. The evolving city and shifting demographics and attitudes, continue to inform the choices of who is represented. Since its naming in 1945, Avenue of the Americas has become home to statuary representing seven Latin American leaders, most recently the Mexican revolutionary and statesman, Benito Juarez. Penelope Jencks' portrait of first lady and humanitarian Eleanor Roosevelt, one of the few statues in the collection of a non-allegorical female, welcomes visitors to Riverside Park's southern entryway, while the African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass is celebrated at the northwest corner of Central Park. In Union Square, a statue of Gandhi, the independence and spiritual leader, has universal appeal as well as special resonance for Indian immigrants. The notion of loss is often at the core of memorialization, and a relatively modest memorial such as Bruno Zimm's Slocum Disaster Memorial in Tompkins Square Park may embody the profound grief elicited by a tragedy of great proportions. War memorials, as noted, constitute a sizeable percentage of the New York City parks collection, as losses have touched all communities. World War I, the Great War or the “war to end all wars,” is the conflict with the most memorials, including nine "doughboy" sculptures that depict the common infantryman, found at community parks from Greenwich Village to Woodside in Queens. The Prospect Park War Memorial by Augustus Lukeman and Arthur D. Pickering, situated at the scenic lakeside, supports bronze honor rolls documenting the sacrifice of more New Yorkers than those who lost their lives in the attacks of September 11, 2001. At its center is a poignant sculptural tableau of an Angel of Death receiving the soul of a dying soldier. The commissioning of monumental sculpture is not without controversy, as debates have raged regarding the appropriateness of a particular subject, park location, or design. For instance, following a groundbreaking and plaque laying ceremony in 1947, a monument in Riverside Park to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust never came to fruition, as no proposed design proved worthy and appropriate for this park (today the plaque and the surrounding landscape in that park serve as a "living memorial" to these events; an extensive educational Holocaust Memorial was dedicated at Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn in 1997). The passing of the great age of monument building and the decline of the traditional sculpture academy have led to new aesthetic approaches, often less representational, and featuring various artistic forms, particularly landscape architecture, as evidenced by the Irish Hunger Memorial in lower Manhattan. At Strawberry Fields in Central Park, John Lennon is honored not by a graven image in bronze or stone but by a bucolic arboretum with the simple but powerful word "Imagine" (derived from Lennon's song by that name) set within a mandala-like mosaic. The result is both specific and universal in its message of peace. The process of creating a public monument in a democratic society is by necessity a messy one, often characterized by compromise that may be at odds with an artist's solitary creative vision. The threshold for acceptance has increased too as the city has become more congested, public space more contested, and in an age of "identity politics" there is less universal agreement about who our common heroes are. In the parks of New York the vast majority of pieces continue to be financially supported through citizen initiative and charitable contributions, causing communities to be invested literally and figuratively. The core purpose of this monuments collection remains the perpetuation of memory through objects of relative permanence that long outlast the events and people they honor. Some pieces may also embody concepts and beliefs which we still uphold while others champion values that seem outmoded. Sometimes the choices of what has been memorialized can with hindsight appear strange and remote, as today's revered personage or cause becomes tomorrow's trivia question (witness the sculpture of poet Fitz-Greene Halleck on Central Park's Literary Walk or the Temperance Fountain at Tompkins Square Park.) The reputation of even the most adulated individual may diminish over time or be reinterpreted (Thomas Jefferson, after all, owned slaves). In 1967, faced with the complex issues and difficulties of permanently occupying public spaces with monuments and artworks, the City's Parks Department embarked in on a new path, in which works of contemporary art of extraordinary diversity in form, material and content have been displayed at park locations for periods up to one year. Since then more than 1,000 projects have been installed at more than 170 parks on a rotational basis, fulfilling much the same purpose as a temporary exhibition in a museum or gallery. This process has provided wider opportunities for display, and permitted greater latitude for park programmers than would be the case with permanent artworks, monuments and memorials. The public's response has often been more enthusiastic for the temporary public art than its reaction for those artworks that are permanently exhibited. With that said, the Parks Department takes great pride in the preservation of its permanent art and monuments collection, seeing this obligation as a pact with previous generations. At one time many of the monuments were in a state of disrepair and neglect, their decline threatening to subvert their meaning of permanence. In the 1930s the Parks Department established a small but dedicated in-house restoration and maintenance crew. By the 1980s, with personnel reduced through City budget cutbacks, the Parks Department found itself overwhelmed with an ever growing commitment. Concerned citizens and organizations led a charge to augment the city's preservation services with private investment and advocacy. The first such program, a joint venture of the Municipal Art Society (MAS), the Parks Department and the Art Commission, was known as Adopt-a-Monument. Launched in 1987, the program solicited individual, corporate and foundation contributions to support the conservation of 20 major monuments in need. One of the first to be treated was Anna Hyatt Huntington's monumental equestrian of Joan of Arc in Riverside Park at 93nd Street. To date the Adopt program has supported the restoration of 37 park monuments. In 1991, under the auspices of the Central Park Conservancy (CPC), a monuments preservation program was launched to address the needs of a collection of 50 major monuments in the park. Each work was conserved, with a dedicated staff and summer apprentices continuing to perform follow up care on an annual basis. The Park's Department's Art & Antiquities division in 1997 created the Citywide Monuments Conservation Program (CMCP), a public-private partnership, modeled after the CPC program, to address holistically the collection throughout the city's parks. The program has restored more than 65 major monuments, and performed care of more than 100 (often annually). More than 100 interns studying historic preservation and fine arts at the graduate level have been trained through the CMCP program, which uses the collection as an outdoor laboratory to prepare the next generation of conservators. The program is premised on providing steady care that ensures the structural integrity of the monuments collection as well as a consistent aesthetic appearance that avoids cycles of decline and renovation. The effort by all of these combined resources and programs has moved the state of the collection from a restoration to a preservation mode. Ongoing veneration of the monuments is supported by numerous community groups, preservation societies, and veterans organizations. The Parks Department seeks too to educate the broadest public possible through active and extensive web content about its collections, to increase the public's awareness, and hence appreciation of the monuments and artworks in their midst. While a particular event may cause a surge of new interest in a specific monument (as when the George Washington, our oldest sculpture, became a rallying point for the public after 9-11), it is our collective responsibility to honor these monuments so that future generations may have a full understanding of the impulses that engendered them and so shaped our cityscape.

William Walcutt. Toppling of King George Statue, Bowling Green, 1857. Oil on canvas. Lafayette College Collection. ×

Henry Kirke Brown. George-Washington, dedicated 1865. Photo by J. Kuhn; taken during 150th anniversary event, July 3, 2006 ×

Philip Martiny, sculptor of spandrel figures; John John Hemingway Duncan, architect. Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, 1982. Granite; 80' x 80' x 50'; archway h 50' x w 35'. Photo by J. Kuhn ×John Quincy Adams Ward, sculptor; Richard Morris Hunt, architect. Seventh Regiment Memorial, 1870. Bronze,and Barre granite; 21'4" x 10'6" x 10'6'. ×Allen G. Newman. The Hiker, 1916. Bronze and North Jay granite; figure 6'7" high; pedestal 6' x 5'10" x 5'10"; plaques 1'8" x 2'6". ×Daniel Chester French, sculptor; Henry Bacon, architect. Lafayette Memorial, 1917. Bronze and Milford pink granite (polished); Bas-relief 10' x 13' ; Stele: 19' x 22' x 8'10"; Terrace: 72' x 35'. Photo by J. Kuhn. ×

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, sculptor; Stanford White, architect. Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, cast 1880; dedicated, 1881. Bronze and Coopersberg (Pennyslvania) black granite; figure 9' high; pedestal with exedra wings: 9' x 17'6" x 9'6". ×

Rafael Ferrer. Puerto Rican Sun, 1979. Cor-ten steel; 22' x 25'6" x 22' at base. Photo by C. Djuric. ×

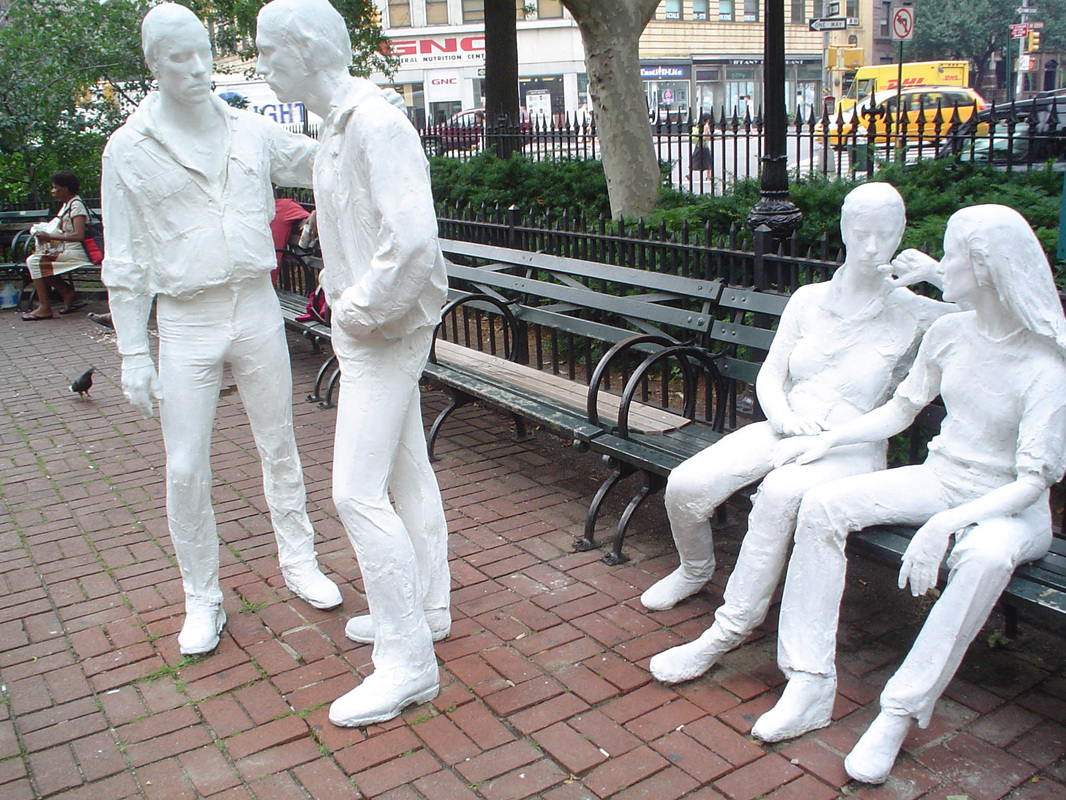

George Segal, sculptor; Philip N. Winslow, ASLA, architect. Gay Liberation, cast 1980, dedicated 1992. Figures: bronze with white lacquer, benches: steel with black paint; group 5'11" x 16' x 7'6"; each bench 16' long; plaque 7 5/8" x 7 5/8".] ×Robert Graham. Duke Ellington, 1997. Bronze; figure 8' high; each caryatid 4' high; each triform column: 10' high; sculpture total: 25' high; upper plaque: 5" x 10"; lower plaque: 2¼" x 7½". Photo by Sara Cedar Miller. ×Elizabeth Catlett, sculptor; Ken Smith, landscape architect. Ralph Ellison Memorial, cast 2002, dedicated 2003. Bronze and deer isle granite; 15' x 7'6" x 6". Photo by S. Drago. ×

Eric Fischl, sculptor; Mark Sullivan, architect. Soul in Flight: Arthur Ashe Memorial, 2000. Figure: bronze; plate: brass; footing: concrete; figure: 14’ high. ×Alison Saar, sculptor; Quennell Rothschild Partners, landscape designer. Harriet Tubman Memorial, cast 2007, dedicated 2008. Bronze and Chinese granite; approx. 13' x 14'. ×

Moises Cabrera Orozco, sculptor; Enrique Norten, architect. Benito Juarez, cast 2002; dedicated 2004. Bronze; 5'5" high. Photo by J. Kuhn. ×Penelope Jencks (figure) / Michael Middleton Dwyer (boulder and foot stone), sculptors; Bruce Kelly / David Varnell, architects. Eleanor Roosevelt Memorial, 1996.

Gabriel Koren (figure) / Algernon Miller (site and fountain designer), sculptors; Quennell Rothschild & Partners, architects. Frederick Douglass Memorial, dedicated 2011. Bronze and granite. Photo by Gabriel Koren. ×Bruno Louis Zimm. Slocum Disaster Memorial, 1906. Tennessee pink marble; 9'2" x 6' x 4'11". Photo by V.Riddick.] ×Augustus Lukeman, sculptor; Arthur D. Pickering, architect. Prospect Park War Memorial, 1921. Group and plaques: bronze; pedestal and wall: Milford pink granite; 18' x 35'. Photo by J. Kuhn. ×

Bruce Kelly. Imagine, 1985. Neapolitan black and white marble, bronze; circumference: approx. 34'3". ×

|